Empathy is a huge word in therapy. It is touted as the cornerstone of emotional intelligence—a key ingredient in developing and maintaining satisfying relationships. Therapists need empathy for clients. Clients often intentionally or secondarily develop empathy for other people in their lives.

[image description: Two babies, with different skin colors, are sitting near each other. The baby on the left is crying. The baby on the right is reaching out to the distressed baby, placing a hand on the upset baby's shoulder. Thanks Scary Mommy.]

Empathy may very well be the driving force behind why some people choose a career in the mental health field. It is a great quality that predicts many positive outcomes. It is inversely related with perceived levels of loneliness, and highly correlated with prosocial behavior. Empathy helps us connect deeply with others. And when it comes to long-term change in therapy, empathy isn’t enough.

Andrew Solomon’s book, Far from the Tree, contains great evidence that empathy and understanding does not cross all areas of difference. Even while our own experiences of oppression, isolation, bullying, and marginalization can develop our capacity for empathy and enhance our ability to see parallels in pain, our pains are not the same. Empathy is not our end goal. It is not our last stop.

“Almost everyone I interviewed was to some degree put off by the chapters in this book other than his or her own. Deaf people didn’t want to be compared to people with schizophrenia; some parents of schizophrenics were creeped out by dwarfs; criminals couldn’t abide the idea that they had anything in common with transgender people. The prodigies and their families objected to being in a book with the severely disabled, and some children of rape felt that their emotional struggle was trivialized when they were compared to gay activists. People with autism often pointed out that Down syndrome entailed a categorically lower intelligence than theirs. The compulsion to build such hierarchies persists even among these people, all of whom have been harmed by them.”

Empathy depends on our existing capacity to understand another person. It depends on having enough personal experiences which we can compare to another person's experiences. Regardless of how skillful we are with empathy, we can never fully understand another person's experience. For example, a pregnancy can be a cause for great celebration, great despair, or anything in between. A loss of a job may be experienced as liberating. Our emotions are often complex and layered. We experience things uniquely. A woman may experience various degrees of sexism and sexual harassment, just as a Person of Color may experience various degrees of racism and systematic oppression. These experiences vary and sting in different ways. Empathy is great for having compassion and tolerance for differences--especially in the people we already love. And even in the people we love, we can misunderstand and miss their pain entirely.

“Positive social emotions like compassion and empathy are generally good for us, and we want to encourage them. But do we know how to most reliably raise children to care about the suffering of other people? I’m not sure we do.”

But what about acquaintances and strangers? Empathy is much harder to activate for a random passerby. Imagine the person who cut you off on your commute today, or the person you saw kicking their dog or yelling at their child. Imagine the person in the wheelchair with a can in their hand on the street corner, or the traveling musician busking for money downtown. Imagine someone with schizophrenia or autism or pedophilia. Imagine someone so different from you that you feel that twinge of aversion and repulsion. Does your empathy still reach that person?

“Relying on empathy means black people faced with horrific levels of police brutality must make white people “feel our pain.” It forces us to stream the bodies of our dead sons and daughters on a loop. It requires there to be dead sons and daughters in the first place. It always demands more spectacles of pain.”

If therapy's aim is to provide healing, then we must consider where empathy falls short. We must look at the lines we do not cross regarding power, privilege, and oppression. We must explore the spectrum of rejection, tolerance, and celebration. Then we can begin to address the intergenerational trauma that is carried from oppressive experiences like racism and the Holocaust--both of which have demonstrated long-term negative health and mental health impacts. Undoubtedly, audism (yes, that is spelled correctly), transphobia, and mental health stigma can have similar impacts.

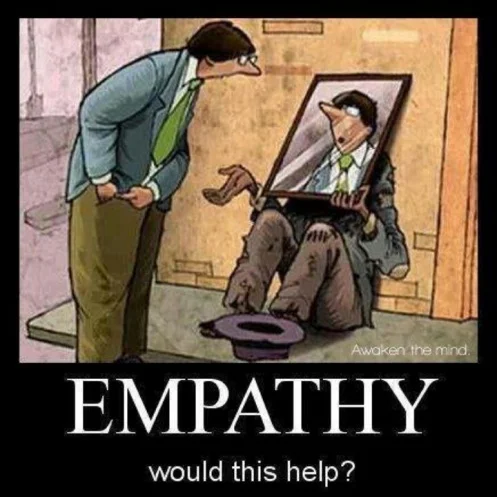

[image description: Cartoon image with caption, "EMPATHY would this help?" In the image, a person is sitting on a street corner in tattered clothes with a hat in front in order to collect money. The person is holding a mirror in front of his/her/zir face in order for the person walking by to see his/her/zir own reflection. Thanks Axis of Logic.]

As a therapist I make a point to read articles and blogs by people from various backgrounds and perspectives. It is a practice that helps me develop my understanding and empathy for people with experiences outside my own reality. Theoretically, this will enhance my capacity to sit with any client who comes into my office. Ideally, understanding and listening to various perspectives and experiences will enable me to conduct sessions non-judgementally, regardless of any conglomeration of symptoms, complaints, behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs that a client presents. A couple of weeks ago, I read this article on why empathy won't save us in the fight against oppression.

Here, Hari Ziyad (also quoted above) points out

“But the belief that empathy can solve the world’s ills relies on the idea that we are all similar enough that someone else’s pain can be understood through the understanding of our own.

What happens when we do not understand our own pain? What happens when we really are different, and substantially so? What happens when those differences cannot be understood? Or, at least, what happens before those differences can be understood?”

[image description: The Pain Measurement Scale, which is often used in doctor's offices. A scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable) with correlating faces, smiling to miserably crying.]

Hopefully, in this case, you can see a counselor who has exceptional practice in his/her/zir own pain and the capacity to be with someone else's pain without denying it, minimizing it, or judging it. Hopefully, you can find someone who will believe your pain, even if they do not comprehend it.

[image description: There are five lines of text that are all crossed out. They read "It's not that bad", "Just be happy", "Don't be sad", "You'll get over it", and "You're overreacting". The final line of text is clear: "I believe you."]

Whether you are a therapist, a therapist-in-training, a client in therapy, or a human interested in self-growth, empathy is a critical part of your ongoing emotional intelligence. It is also critical to continue to examine and challenge your assumptions, biases, fears, and internalized stigmas regarding who has value and what makes them valuable. As Michelle Alexander addresses is The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, which of your values and judgments justify legal, social, and economic boundaries between “us” and “them”? Remember that person you called to mind earlier, the one who elicited your aversion? This is when our empathy takes a back seat, no longer activating our mirror neurons.

[image description: A graphic art image of two human shapes looking at each other. Inside their heads, there are blasts of color, representing neural activity. Some of those blasts of color (neural activity) are bridging the physical gap between the two people, representing mirror neurons. Thanks Psychology Today.]

Luckily, mirror neurons are activated through consistent interaction and eye contact. Therapy, therefore, can be a be a new frontier for moving beyond empathy. When you are in a therapy office, sitting across from another human, you have a unique opportunity to engage with someone who is entirely similar and entirely different from you. Whether you are therapist or client, take this opportunity to breathe and to engage with the humanity in the person across from you. Regardless of the difference, confusion, frustration, joy, relief, and support that arises in the therapeutic relationship, return to the humanity in yourself and the person across from you again, and again. It is an art and a practice. Breathe, notice, and return.

*Note for clients: If your therapist does not have the capacity to stay present with your pain, especially if you identify with one or more marginalized identities, call them out and/or find a new therapist.

*Note for therapists: If your client identifies with one or more marginalized identities and expresses a lot of anger and pain, it is not personal. If it is too much for you, get supervision and/or refer them to another therapist.

![[image description: The Pain Measurement Scale, which is often used in doctor's offices. A scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable) with correlating faces, smiling to miserably crying.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/557498d6e4b046e672b1529e/1441928258497-4JJEF9PPAJ8IMHXIS3TO/image-asset.jpeg)

![[image description: There are five lines of text that are all crossed out. They read "It's not that bad", "Just be happy", "Don't be sad", "You'll get over it", and "You're overreacting". The final line of text is clear: "I believe you."]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/557498d6e4b046e672b1529e/1441928549577-36LFCG9EMLXM8JBAVUIY/image-asset.jpeg)